By Lisa Taylor

When the pandemic hit and offices around the world closed, inboxes filled with messages declaring the Future of Work had arrived. Employers were worried. Did employees have the technology they needed at home to remain productive? How would remote management of staff, projects, and resources play out? Who should be considered essential for operations and who shouldn’t be? How do you maintain culture when no one can see each other in person?

The assumption: Technology and age

From a demographic perspective, many assumed that older workers would struggle with remote work due to a perceived lack of technical skills. Boomers make up a large chunk of the workforce; their ability to adapt was critical. If they couldn’t adapt, would productivity drop to dangerous levels?

In The Talent Revolution: Longevity and the Future of Work, I explore these (mis)perceptions that older workers are less technologically savvy than their younger counterparts and explain that in Challenge Factory’s work:

“We hear comments about boomers’ limited technological abilities all the time, and while it is true that younger generations have been born into a tech-enabled world, most boomers have migrated to today’s technology with only a slight accent to indicate it’s not their mother tongue. In fact, most make a serious effort to stay ahead of the curve, realizing that if they do not, they will be marked as archaic” (2019, page 80-81).

In COVID-19 times, once we had a chance to step back and assess how the transition to widespread remote work actually unfolded, many were surprised to find that while age was an issue, it turned out that younger workers were struggling more.

The key factor for thriving in the abrupt change to remote work environments wasn’t tied to the adoption of tech. It was the length of time a person was at the company before the pandemic hit. If you, as an older worker, had been with your organization for a long time and had built solid, ongoing relationships with your coworkers, all you had to do was learn to use Zoom and the social connections did the rest. Most older workers thrived. In fact, new studies are highlighting the number of retirees who are re-engaging in work activities now that commuting into an office every day is no longer required.

Widespread assumptions about what was coming, like the effect of age on adapting to remote work, were incorrect. In this case, most didn’t see that human relationships were at the heart of this equation—not technology. If we had time to stop and check our assumptions, we may have picked up on this. We know that collaboration tools like Slack can be learned quickly. People, though? People take time, shared experience, a few laughs, a few well-executed projects together.

Leaders and teams can get so caught up in coping with massive change that they act upon assumptions. But we can’t always trust our gut when the stakes are so high.

The equation: Possibility, desire, and urgency

I’m often asked if the pandemic has merely accelerated the implementation of previously known trends, or if the Future of Work is now completely different than what was imagined prior to 2020. I really like this question because it’s a great antidote to the wave of the “Future is Now” thinking, and it reminds us to “zoom out” from this moment to ask what the real impact will be.

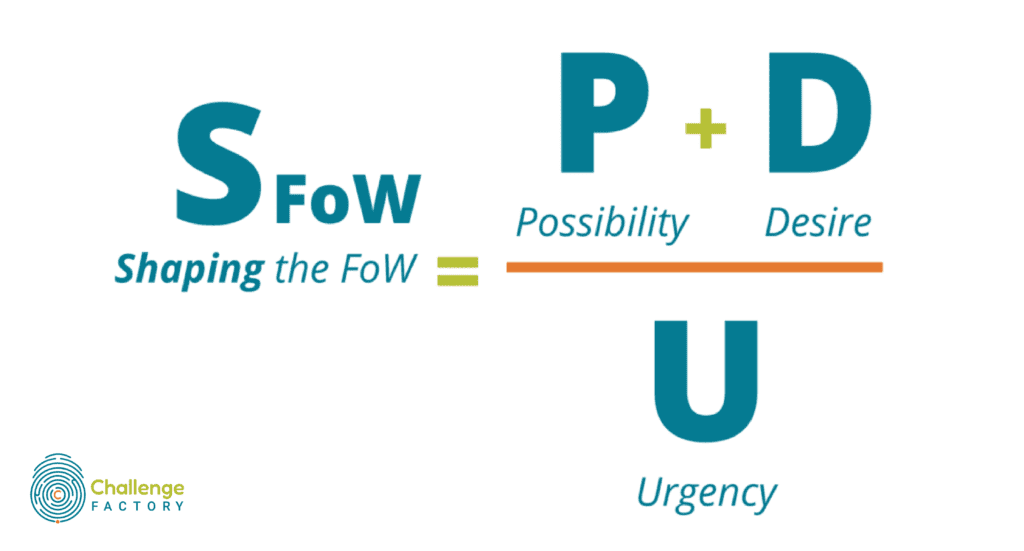

In considering this question, I recently came up with an equation, an association of ideas, that summarizes my thinking about the Future of Work:

The pandemic showed us that many practicalities become possible when the need is great. Necessity is indeed the mother of invention and we’ve all been innovating like crazy. Much of what we hear about the Future of Work assumes that because we’ve increased the “possibility” score in so many ways, from technological adoption to remote work arrangements, we have catapulted ourselves into the future.

But this only accounts for part of the equation. It ignores the equally important constant of what matters to us—what we want—and has us working with an urgency that is appropriate for a crisis but ultimately unsustainable.

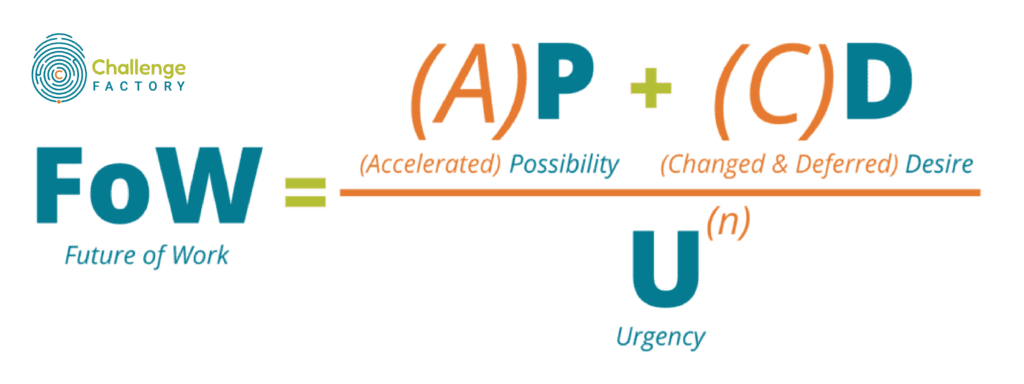

If we were to measure the Future of Work as presented by COVID-19, the equation would look like this:

During the crisis, our equation became unbalanced: the higher the urgency, the lower our ability to make informed predictions. Current declarations that we’re experiencing the Future of Work right now are problematic. We need to bring the equation back into balance first. We do this by focusing on (1) what we have learned since the pandemic began, and (2) what we want and desire as part of our Future of Work. We need to turn down the urgency and take that step back to reflect.

While we’ve seen what can be possible, we’ve also put many personal and organizational interests on hold. Psychologists remind us that burnout and exhaustion are expected in times of crisis, and these are only exacerbated by a work environment where tasks are more challenging, the needs are greater, and the time-to-impact is difficult to predict. The first step to balancing the equation is recognizing that we need ways to address what we consider urgent and how we lead teams to deal with very challenging, strategic issues without creating exponential stress.

The pace: Acute and chronic challenges

It’s an odd circumstance to have published a book on the Future of Work six months before COVID-19 made its first global appearance. The hardcover sits on my desk and serves as an unalterable reminder of my thinking in the spring of 2019. That seems like forever ago.

But within The Talent Revolution‘s pages, I lay out models and tools that help leaders manage pace and urgency. Using a healthcare analogy, I call for leaders to pay attention to the difference between crisis/acute issues and long-term/chronic concerns:

“Technological change is a constant and continual evolution…a chronic condition, important, persistent, and perpetually in need of attention. In contrast, workforce change is often treated as an acute condition requiring urgent and immediate action to deal with a clearly defined episodic event. However, both technological change and workforce change are chronic organizational conditions” (2019, page 13).

As we emerge into a post-COVID future, how we lead and the pace we set is more important than ever. Is every day a sprint to end a crisis or are we setting the pace for our teams to run the marathon of shaping the future?

The Future of Work is not merely an expression of what is possible. Leaders need to spend time reflecting on what they want for the future of their organization and how to return to a more sustainable pace of change. Long after the pandemic has passed, there will be a need for this type of forward-facing future planning.

How will your organization rebalance its Future of Work equation?

We would be thrilled to help you through the process. Contact us to learn more about working with Challenge Factory.